I had the pleasure of meeting Liese Sherwood-Fabre when we were fellow panel members at a mystery...

How to Survive a Pandemic from Polar History’s “Wicked Mate”

I was recently asked if the coronavirus pandemic had changed what readers want from mystery authors.

Maybe.

Right now, I think readers appreciate a good tale of overcoming the odds.

That’s why polar history resonates with me right now. The early exploration of Antarctica and the North Pole regions is replete with true stories of resilience and fortitude when all hope seems lost. The exploits of Ernest Shackleton, Douglas Mawson, and Roald Amundsen are the stuff of legend.

One of the best known episodes from the so-called Heroic Age of exploration is the competition between Robert F. Scott and Roald Amundsen to be first to the South Pole. To recap, in 1912 Scott led a British team on a grueling march halfway across Antarctica to the South Pole, only to find that Norway’s Amundsen and his dogsledders had already come and gone.

Scott’s entire team died of illness and starvation on the return journey. Amundsen’s team dumped excess food as they sprinted back to their expedition’s hut.

There are a thousand lessons to be learned from the Scott-Amundsen race. But if you want to survive a pandemic, study the “Northern Party,” an all-but-forgotten sideshow to the Scott disaster.

It’s one of the most amazing survival stories you’ve never heard of.

Meet the “Wicked Mate”

Victor Campbell was a 34-year-old lieutenant in the Royal Navy when he accepted Scott’s invitation to join the British Antarctic Expedition. Campbell was named First Officer of the expedition ship Terra Nova and third in command overall (after Scott and Lieutenant Edward “Teddy” Evans.)

Victor Campbell in 1913

The rest of the British Antarctic Expedition were British Navy officers and sailors, civilian scientists, a Norwegian ski expert, and a Russian dog handler.

The expedition’s primary mission was to plant the Union Jack on the South Pole. Scott’s Southern Party would march south from basecamp at Cape Evans.

The secondary mission was scientific discovery. Most of Antarctica was unmapped and untapped; a blank slate. A host of scientific programs was laid out that could be completed within range of Cape Evans.

The exception was the much smaller Northern Party, led by Campbell. This 6-man team would focus on geological discovery, mapping, and weather observations in the area south of New Zealand.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, in his gripping account THE WORST JOURNEY IN THE WORLD, wrote “Lieutenant Evans . . . was in charge . . . to cement together the rough material into a nucleus which was capable of standing without any friction the strains of nearly three years of crowded, isolated and difficult life, ably seconded by Victor Campbell . . . in whose hands the routine and discipline of the ship was most efficiently maintained. I was very frightened of Campbell.”

Campbell’s nickname of “Wicked Mate” came from the “mixture of respect, awe, admiration, trust, and finally affection” of the men who served under him, according to H.G.R. King, the editor of his diary. The Wicked Mate had a reputation for shyness but it came with a sense of humor, along with imperturbability and discipline. He was comfortable with authority.

Those traits would save lives.

Forging a team

Besides Campbell, the Northern Party was comprised of geologist Raymond Priestly, Royal Navy surgeon Murray Levick, and Petty Officers G.P. Abbott, F.V. Browning, and H. Dickason. The group spent most of 1911 at Cape Adare where the 1899 expedition led by Carstens Borchegrevink was the first to spend a winter on the continent.

Priestly wrote in his book ANTARCTIC ADVENTURE, “We left [Cape Adare] in January 1912 a well-knit party, reasonably satisfied with the scientific record we had achieved, to which every one of the six had made notable and essential contributions.” Cape Adare’s near-constant blizzards hampered their scientific work yet forged a team spirit of ingenuity and inventions that ranged from a makeshift alarm clock dubbed a “Carusophone” to a face mask to prevent frostbite.

More importantly, the now tight-knit team was accustomed to Campbell’s habits of naval discipline.

The expedition ship Terra Nova left its winter berth in New Zealand (to avoid being caught in pack ice) and took them from Cape Adare to the aptly named Inexpressible Island. The plan was for the Northern Party to continue scientific discovery there for a few weeks. Terra Nova would return in February to ferry them to the Cape Evans basecamp 230 miles away.

Ice blocked the Terra Nova from returning. As February turned into March and winter descended with furious wind that tore their canvas tents, Campbell realized the Northern Party was stranded.

Remember, this was 1912. They were at the bottom of the world. No electricity. No communication.

No help.

How could six men survive the 9-month polar winter, with bone-cutting temperatures and days of 24-hour darkness, with nothing more than a couple weeks’ worth of dried food and rapidly disintegrating tents?

Priestly summed up the situation: “It was evident that three things were absolutely necessary, and perhaps only three. We must have light, shelter, and hot food.”

The Sooner the Better

“The outlook is not very cheerful.” Campbell’s diary, 16 March 1912

Campbell quickly recognized that circumstances had changed and made no attempt to sugarcoat the situation. He embraced the brutal truth fast and didn’t waste time on self-pity or wishful thinking.

As early as 26 February, he set aside the remaining rations, fuel, and clothing designed for polar sledging, worried they would be needed for the trek over uncharted territory to Cape Evans. For all Campbell knew, the Terra Nova had sunk or was trapped in ice somewhere in the Antarctic Circle and he had to get his team back to basecamp on his own.

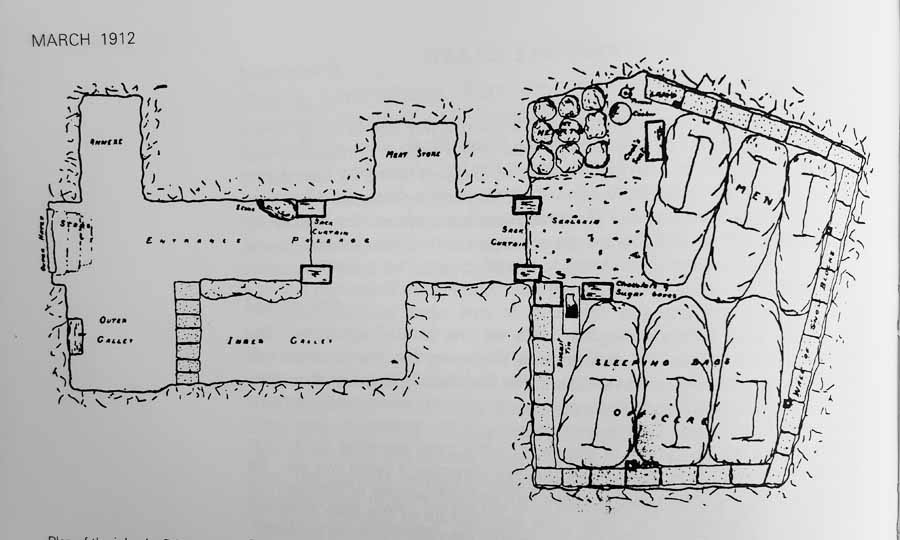

The next day, with three off exploring the island on a scientific trip, Campbell and two others began hacking a cave out of solid ice to serve as winter shelter for all six men. The result was 9 x 12 feet, with a max height of 5’6”. The tunnel to access it was 2’6” x 1’6”.

Diagram of cave by expedition geologist Raymond Priestley

Campbell also calculated how many penguins and seals they’d need to kill before the full onset of winter when the animals took shelter and it was too dark to hunt.

By 19 March, the ice cave was home and the perpetual hunt to stock the larder despite frostbite and blizzard was on. The cave gave them the light, shelter and hot food Priestley deemed essential but not much else. A diet of meat, seaweed, and saltwater began to take a heavy toll on digestive systems. Seal blubber was used as fuel, so the floor—and the men—quickly became coated in greasy soot.

As blizzards raged outside and freezing temperatures reigned inside, the men spent most of their time in sleeping bags. Following Navy tradition, Campbell bisected the tiny space into “decks” for officers and sailors. An unwritten law decreed that what was spoken in one deck was not “heard” in another. When Campbell and Levick were seriously worried about Browning’s health during the winter, however, they passed notes.

Lesson from Campbell: The sooner you recognize that the situation is changed and adapt, the greater your chances of getting ahead of negative consequences. Refuse to see that the situation you expected has been overtaken by events? You risk a cascade of secondary problems.

Critical routines

“We take it in turns to be cook and messman.” Campbell’s diary, 9 April 1912

By June the sun had completely disappeared. Tucked inside the dark cave, with only crude blubber lamps for light, Campbell used routine to hold insanity at bay and maintain a sense of passing time:

Duty roster: Three teams of two men took turns as the day’s cook and messman, or cook’s helper. When on duty, the team was responsible for preparing meals, cleaning up, gathering snow for water, etc. The workday began at 7:00 am with breakfast preparations. Dinner was at 5:00 pm.

Food: To augment the diet of seal and penguin, they doled out minute portions of sledging biscuit—like a heavy graham cracker. Cocoa five days of the week. On Sunday they had 12 lumps of sugar and tea, which was reboiled for Monday, and then dried to be used as pipe tobacco. The last day of the month was celebrated with raisins, as were birthdays. On Wednesdays and Saturdays, they each got 1 ounce of chocolate. Birthdays were celebrated with extra treats as well.

Events: Singing concerts (a “sing-song”) took place Saturday nights. Campbell held a church service on Sundays “which consisted of my reading a chapter of the Bible followed by hymns.” Levick read aloud after dinner each night. When the books ran out, he gave lectures on human anatomy.

Priestley wrote: “The celebration of all special occasions proved to be a godsend . . . such gala days were looked forward to for a week or more and remembered for as long; they seemed to break the monotony of winter.”

Lesson from Campbell: Locked down by the pandemic? Don’t let your days become one big long blur. Create order and routine. Celebrate milestones, even in a small way. This approach creates a sense of control and forward progress.

Continuous improvement

“Levick some days ago designed a new stove which we call ‘The Complex’ in opposition to our old one, ‘The Simplex.’ The reason the ‘Complex’ did not catch on with the rest of us he put down to professional jealousy, but today I came in to find the designer using the old ‘Simplex’ while a much battered ‘Complex’ lay outside on the drift where it remained the rest of the winter.” Campbell’s diary, 7 June 2012

Throughout the winter, the men sought to improve the situation, going above and beyond the ingenuity shown at Cape Adare.

They created:

- An “outhouse” by the entrance.

- A ventilation system made of biscuit tins, snow blocks, and a bamboo sledge pole to prevent carbon monoxide poisoning and smoke inhalation.

- A variety of stoves using blubber for fuel that “reduced preparing and cooking the food to a fine art.”

- Systems for cutting, storing, and transporting meat for the trek to Cape Evans.

Priestley wrote about their improvements saying, “As one difficulty after another disappeared we became more and more convinced that we were going to pull through, and this although we had at this time only enough seal to keep us going on half-rations until the end of July.”

Lesson from Campbell: You can always make your immediate environment better. No matter where you are, look around and make small improvements that support your goals. Each improvement is a force multiplier.

Get Ready for the Next Step

“We have been discussing our best route down, whether to go round the Drygalski [Glacier] on the sea ice or over the tongue. I, myself, don’t think the ice can be depended on round the Drygalski; it runs so far into the Ross Sea.” Campbell’s diary, 1 June 1912

At the end of September, the Northern Party left the ice cave on Inexpressible Island and struck out for Cape Evans. There was no way to know they would encounter sand-like snowdrifts, waist-high sastrugi ice waves, pancakes of sea ice, and the dangerous crevasses of the Drygalski Glacier.

Campbell had the fresh items he’d held in reserve for the journey. In every other way, the odds were against all six men surviving a 230-mile journey over uncharted territory.

But they prepared:

- All the men were weak and suffered from swollen feet and ankles from months spent lying down. A stretching and isometric exercise regime prepped them for distance walking.

- Browning was seriously ill with ptomaine poisoning. Levick experimented with his diet, which necessitated sacrifice for others but saved his life.

- The sledges were damaged from wintering in snowdrifts outside the cave, but essential for hauling supplies. They brought them inside and repaired them using rudimentary tools.

- Their sleeping bags had molted and were covered in grease. Tents had been shredded in March. Repairs were made to the extent possible.

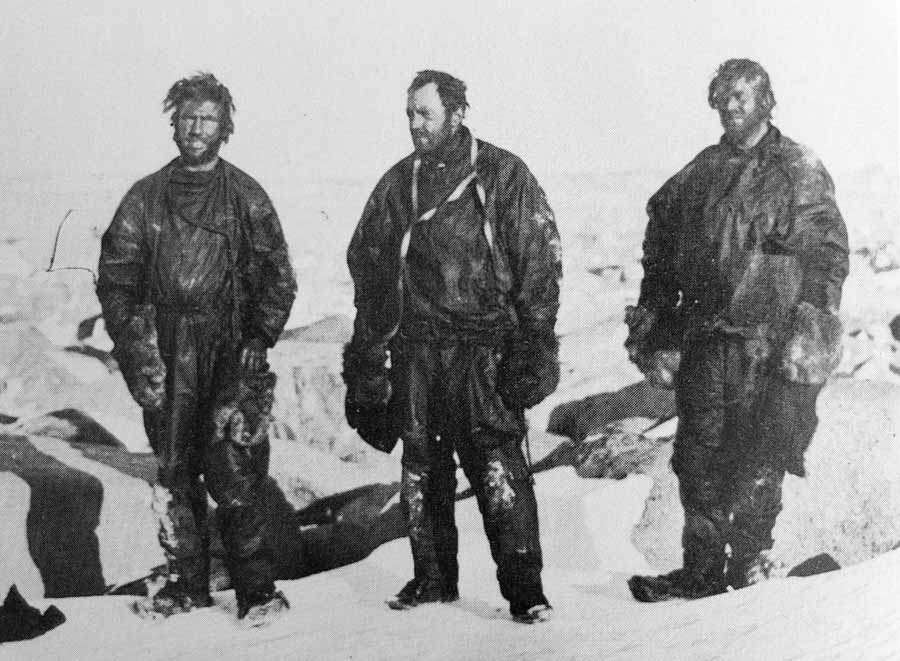

Abbott, Campbell and Dickason leaving the ice cave, 30 Sept 1912

Priestley, Levick and Browning leaving the ice cave, 30 Sept 1912

Priestley’s account of the journey is harrowing. Roped like horses to pull the heavily burdened sledges, they burned more calories than they could take in. Starvation dogged them. At times, the surface was so difficult they resorted to relaying supplies. The unwieldy sledges sometimes dragged them over the ice or got stuck in crevasses.

Only the routine, discipline, and ingenuity they had established during the winter saved their sanity and pushed them on. “Our tempers had stood an almost unparalleled strain during the past winter,” Priestley wrote. “And stood it successfully; we knew each other more thoroughly than most men ever know their companions.”

After almost a month, they found food depots left by other members of Scott’s expedition. The fear of starvation was finally banished.

Lesson from Campbell: Work on your health and optimism. Uncertainty will always be with us. There is always going to be another hurdle. Time spent preparing is never wasted time.

And Afterwards

The Northern Party arrived at Cape Evans on 6 November, only to hear that Scott’s Southern Party had never returned. They would not know what happened until later that month when a search party stumbled in, having found Scott’s tent and the frozen bodies of Scott, Edward Wilson and Henry “Birdie” Bowers. The diaries of the dead men told of losing the race to the Pole and the tragic journey which ended 11 miles from a food depot.

The Terra Nova returned to Cape Evans on 11 February 1913 and brought the survivors back to civilization. The British Antarctic Expedition was over.

The Wicked Mate was honored for his polar service. Campbell commanded fleet vessels with distinction during World War I, including at the Battle of Jutland. He retired in 1922 with a chest full of medals, moved to Canada, and was largely forgotten by historians.

Let’s not make that mistake twice.

All photos from THE WICKED MATE: The Antarctic Diary of Victor Campbell, edited by H.G.R. King

You may also like

Author to Author with Liese Sherwood-Fabre

Best Books to Read According to Contest Judges (and me!)

Today I’m sharing 9 books by friends of the Mystery Ahead newsletter (and 1 by yours truly) that...

Elections This Year are the Stuff of Fiction

In BARRACUDA BAY, the upcoming Detective Emilia Cruz mystery set in Acapulco, elections for mayor...

CARMEN AMATO

Mystery and thriller author. Retired Central Intelligence Agency intel officer. Dog mom to Hazel and Dutch. Recovering Italian handbag addict.